‘To all those who voted for us for the first time' in December, the newly elected Prime Minister made a promise – to ‘unite and level up' the UK. This was widely interpreted as a promise to invest in formerly Labour ‘Red Wall' constituencies in the North of England who had voted Conservative in December 2019. Yet whilst there are significant gaps between the North and South, place-based inequalities do not fall neatly either side of a dividing line. When the government locked the nation down to prevent the spread of COVID-19 just a few months after the election, the UK economy suffered a huge and regressive shock, with GDP plummeting 20%. This has entrenched existing inequalities and redoubled the need for levelling up, making it especially important that the government get it right.

Boris is talking about it all the time, isn't he? Levelling up the North and the South and poorer areas and richer areas. Seems to be the theme at the moment, doesn't it? – CPP focus group in Bury

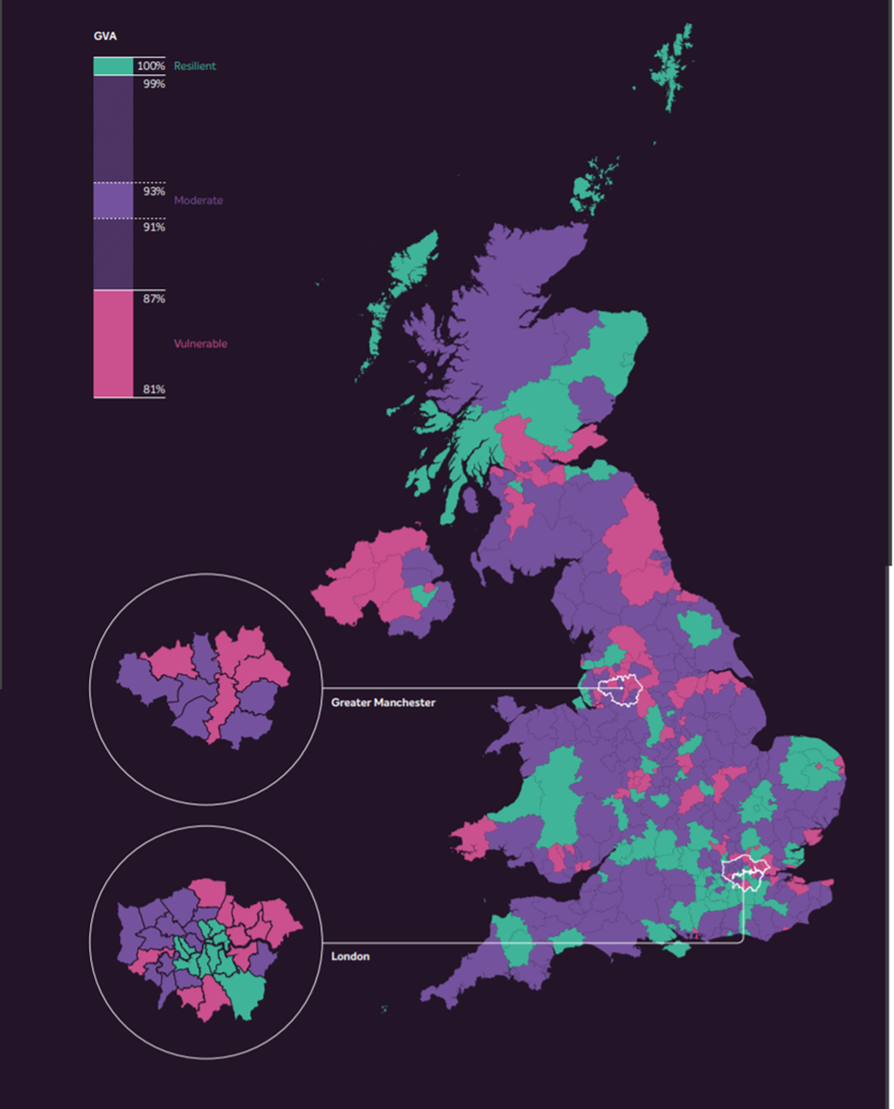

In the Centre for Progressive Policy's (CPP's) recent report, Back from the Brink, we identified 87 places that are vulnerable to long term economic damage due to COVID-19. These places were characterised by large manufacturing sectors, high unemployment, low levels of skills and lengthy recoveries from the last UK recession. Manufacturing features due to the large contraction predicted by the OBR (55%) coupled with its importance for certain economies - it made up 28% of output in the 20 worst hit local authorities. We find that COVID-19 will exacerbate place-based inequalities, including in the Red Wall of traditionally Labour-voting areas. Nearly half (46%) of the 87 vulnerable places are in the North of England or the Midlands, and none of the local authorities in the North East could be classified as resilient.

But our analysis shows that these are not the only places that will need support. There is significant diversity of resilience within regions and many of the most vulnerable communities are also in London and the South East. One in three local authorities in Greater London are predicted to be vulnerable, due to high their unemployment rates and the time that it took them to recover from the 2008 financial crisis.

We also found that some northern communities, such as The Wirral and Sefton, are likely to be more resilient than average, due to the sectoral make up of their economies, and the fact that bounced back quickly after 2008. Sefton, for example, is relatively protected from the economic shut down due to its small manufacturing sector and large public administration and defence sector. HMRC data shows that the proportion of jobs that have been furloughed in these areas is lower than the national average.[1]

Outside of North England, communities along the east coast and in South Wales are predicted to be vulnerable to permanent output losses. Some of these places, such as South Wales already have relatively low healthy life expectancy and have experienced very high rates of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 people, which has put additional pressure on public services. Northern Ireland also has one of the highest proportions of vulnerable places due to a large percentage of the population having no formal qualifications, which CPP analysis found to be associated with larger output losses and higher unemployment after 2008.

It is clearly not as simple as North versus South - even Jim O'Neill, the Vice Chair of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership, agrees. The principle of levelling up must be broader, promoting inclusive growth in all nations of the UK. It must also tackle inequality within places as well as between them. CPP's Inclusive Growth Index highlights significant variation within combined authorities boundaries and the subsequent opportunity that these new levels of government have to ensure that no areas are left behind. Our latest analysis has shown that deprived city districts in London, Glasgow and Belfast need as much attention as those in Manchester, Newcastle and Birmingham and that levelling-up policies must also cover eastern coastal towns, the Scottish lowlands, industrial and post-industrial towns in South Wales and rural communities in the west of Northern Ireland.

Whilst the Chancellor has said the government remains committed to levelling up, COVID-19 has put a question mark over the spending plans announced in March. New transport investment was announced in May alongside an upgrade of the A66 - a key northern road link. The geographical distribution of this new funding is unclear, and the government must be careful to allocate based on need, rather than lazily directing towards the North for the sake of the optics. It may be that Red Wall towns are most in need of investment, but decisions must be based on the kind of data-driven, place-based evidence CPP presents here and elsewhere. Directing investment in both physical and social infrastructure towards vulnerable places is an essential step towards greater equality and the government must not leave Hastings or Gravesham behind, just because they happen to be in the South East.

Rosie Stock Jones is a senior research analyst for the Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP)

[1] The Wirral and Sefton both have furlough rates of 21%, which is lower than the national mean and median rate of 23%. CPP calculations based on HMRC data.