David Ayre considers if councils will have the capacity and resilience to be able to respond to the call for more social homes, and says radical change is needed that will take time to implement

The Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee has said that 90,000 new social homes must be built every year to meet national need, estimating that this will cost an extra £10bn in grant. However, for 40 years, government policies towards social housing have ranged from lukewarm to positively hostile.

Councils have an historic pedigree when it comes to building homes, making the largest contribution to the last great housing crisis in the years following the Second World War. The number of council homes grew to a peak of 6.5 million by 1980, representing more than 30% of all housing stock. Ironically, this peak in the number of council homes was just a year after the election of the Thatcher Government, whose policies would soon take aim at this vital sector. One such policy was the introduction of Right to Buy, which failed spectacularly in its aim to increase owner-occupiers of property.

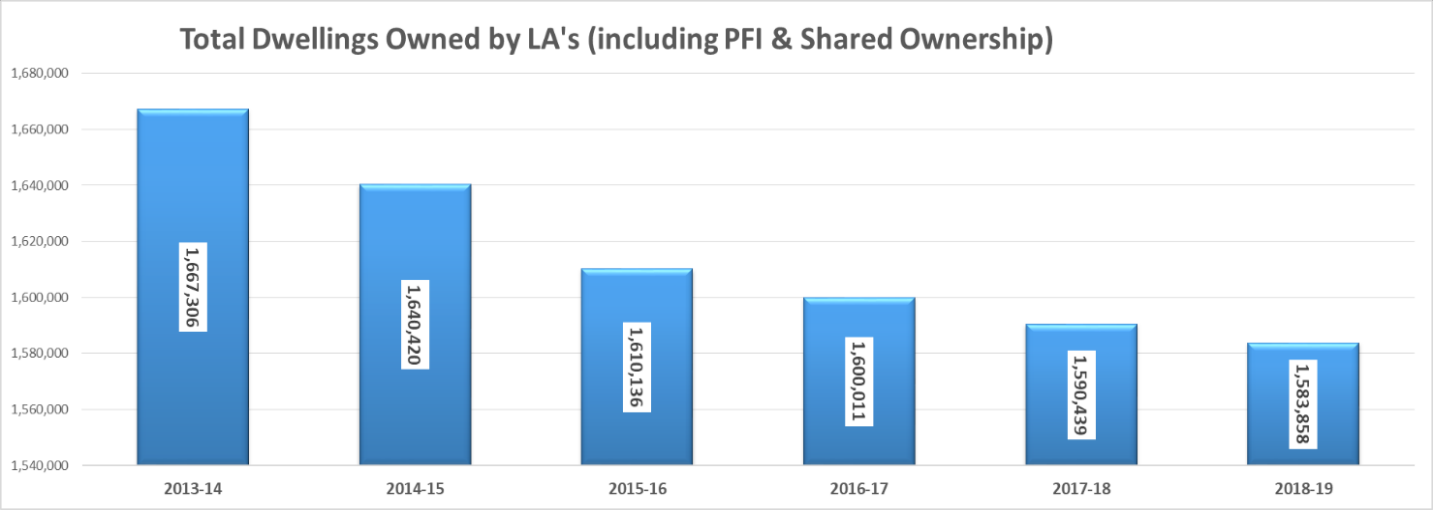

More than 40% of council houses sold under Right to Buy have ended up in the hands of private sector landlords. The Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government's (MHCLG) annual English housing surveys show that as council houses were sold and not replaced, the proportion of households in the social rented sector fell from 31% in 1980 to 17% in 2013/14 where it now remains. Analysis from CIPFA Housing 360 shows that from 2013-2018, the total amount of council housing stock declined by 5%, but with distinct regional variation. The North East has seen the highest loss of stock (nearly 19%), with the South East showing just over 1% loss.

As a result of failure to replace sold-off council homes, rather than a marked increase in home ownership, we see a notable increase in private rentals. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the proportion of private renters was steady at 10%. However, the sector has more than doubled in size since then, with 2.5 million more households in the private rented sector than in 2000. By 2015-16, 4.5 million households were renting in the private sector, representing 20% of all households in England. Meanwhile, there were over 1.2 million households on average on council house waiting lists between 2013 and 2018.

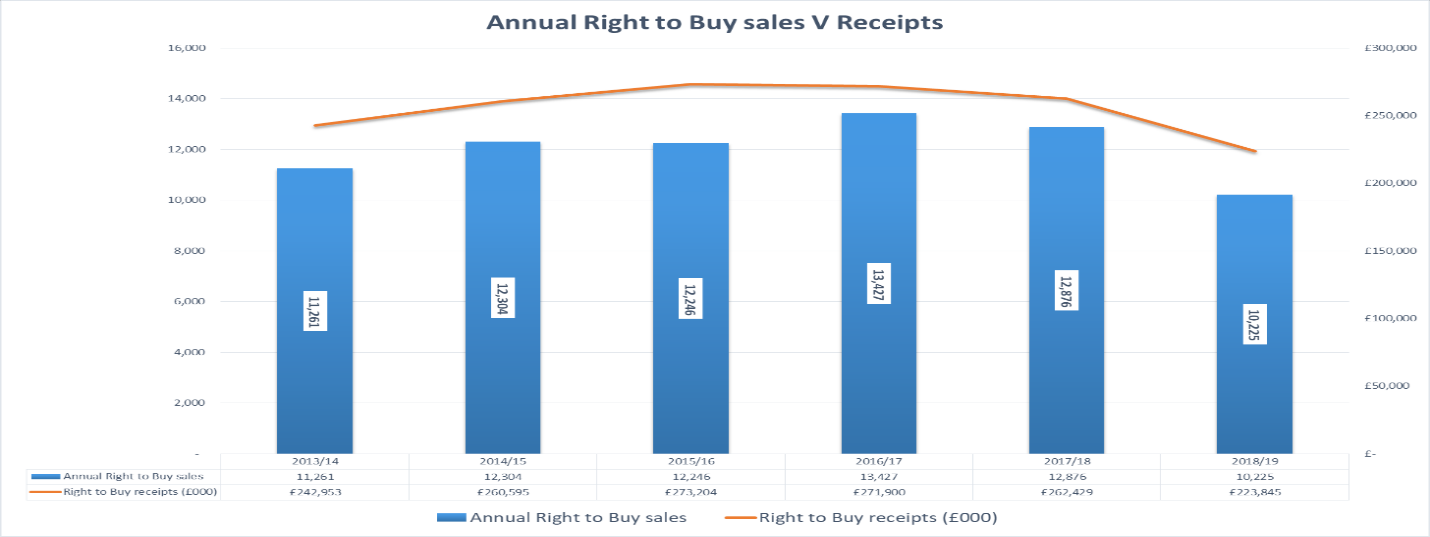

Right to Buy got a second wind from the Cameron-led coalition Government in 2012. An increase in discounts saw almost 13,500 sales in 2016/17 before a gradual decline. A further commitment was introduced that for every additional sale (above the original baseline forecast under the Self-Financing Settlement), a new affordable home would be provided through acquisition or new supply. Councils could also enter into an agreement with government to retain these additional sales receipts to fund the provision of replacement stock.

Unfortunately, the system was designed to make any commitment to replace homes sold under Right to Buy with replacements impossible for councils to deliver. Under the terms of the Local Government Act 2003, local authorities must spend retained Right to Buy receipts within three years, with receipts funding no more than 30% of a replacement unit. Receipts that can't be spent in three years must be returned to MHCLG, together with interest of 4% above base rate, to be spent on affordable housing through Homes England or the Greater London Authority. Statistics from March 2018 showed for the first time that while the overall number of homes available for social rent had increased, councils had been unable to build enough Right to Buy replacements to match the pace of sales.

So what are the implications for households and the wider community? The most obvious is the cost of housing. On average, private renters are paying double the rent of social housing tenants. Furthermore, not replacing sold social housing has contributed to inflated house prices, creating conditions in which home ownership has become unaffordable for large parts of the population.

The decline of social housing and the growth of the private rented sector also impacts on health outcomes. In 2015, 17% of private rented homes had a category 1 hazard (excess cold or fall hazards). This compared with 13% of owner-occupied homes and 6% of the social rented sector.

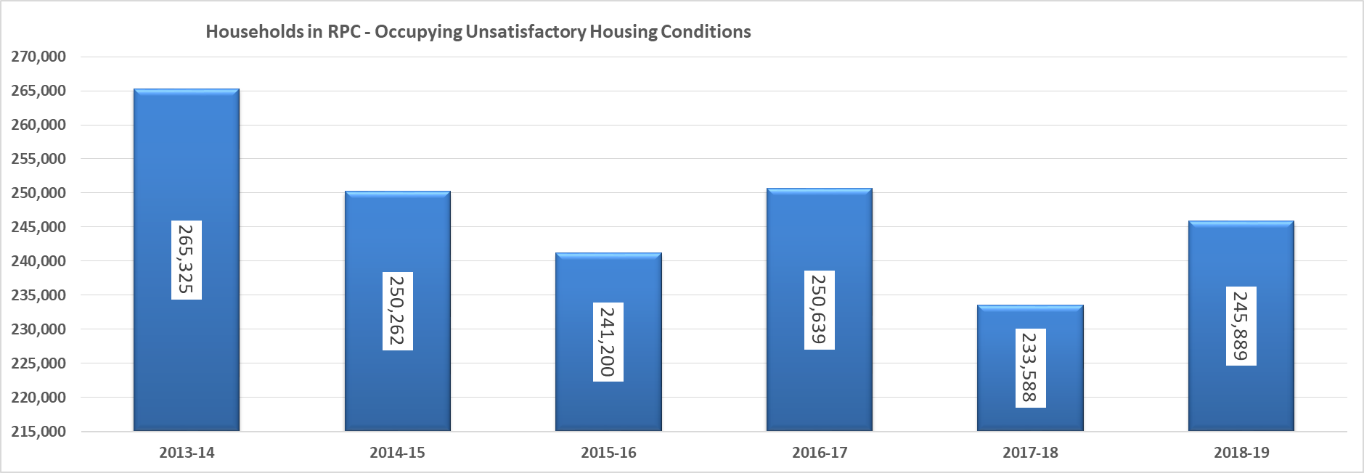

Within the private rented sector, households on low incomes and those supported by housing benefit are more likely to have a category 1 hazard in their home. The same is true of households with a disabled, elderly or long-term ill person. Housing 360 shows that the number of households on council waiting lists living in unsatisfactory conditions have almost increased to 2014 levels.

An estimated 320,000 people are homeless in the UK, according to the research by Shelter. Approximately 726 people died while homeless in England and Wales in 2018, up 22% on the previous year. Rough sleeping is one of the greatest determinants of poor health and one of the most visible consequences of the housing crisis.

Local authorities have been powerless to respond effectively due to regulatory restrictions. We have already seen the impact of Right to Buy on the changing trends in tenure, but this in isolation cannot account for the rapid rises in homelessness and rough sleeping. The Housing Monitor produced by Crisis lays the blame for this on a combination of housing benefit cuts, the benefit cap, the freeze in benefits and the delays in payments of Universal Credit.

That's not to say nothing positive has come from central government in 40 years. The 2017 White Paper Fixing our broken housing market recognised the reality facing most people - the market could not make housing available to those who could not afford it.

Theresa May's Government recognised that the housing market had failed to deliver quality homes for thousands of citizens. The White Paper brought in the Help to Buy scheme, as well as additional duties, powers and funding for councils through the Homeless Reduction Act 2017. May's Government also recognised the role of councils by lifting the borrowing cap on Housing Revenue Accounts (HRAs) – signalling the need for councils to start building homes for social rent once again.

Unfortunately, the new Boris Johnson-led Government has given mixed messages on social housing by increasing the cost of borrowing through the Public Works Loan Board. So where does this leave councils in their transformation of social housing? CIPFA's Housing 360 analytics tool shows that there is a huge amount of work to do.

Authorities are struggling from the decline in social housing due to Right to Buy. While there was a period of higher income from Right to Buy receipts between 2013-2016, 75% of the income generated continues to be returned to the Treasury, making it difficult to invest in new stock. Some councils who have transferred stock to Arm's Length Management Organisations (ALMOs) are considering bringing the service back in house if their ALMO is showing limited signs of capacity to build new homes at scale. Some councils who already have an established HRA have started to include house building in their 30-year business plans.

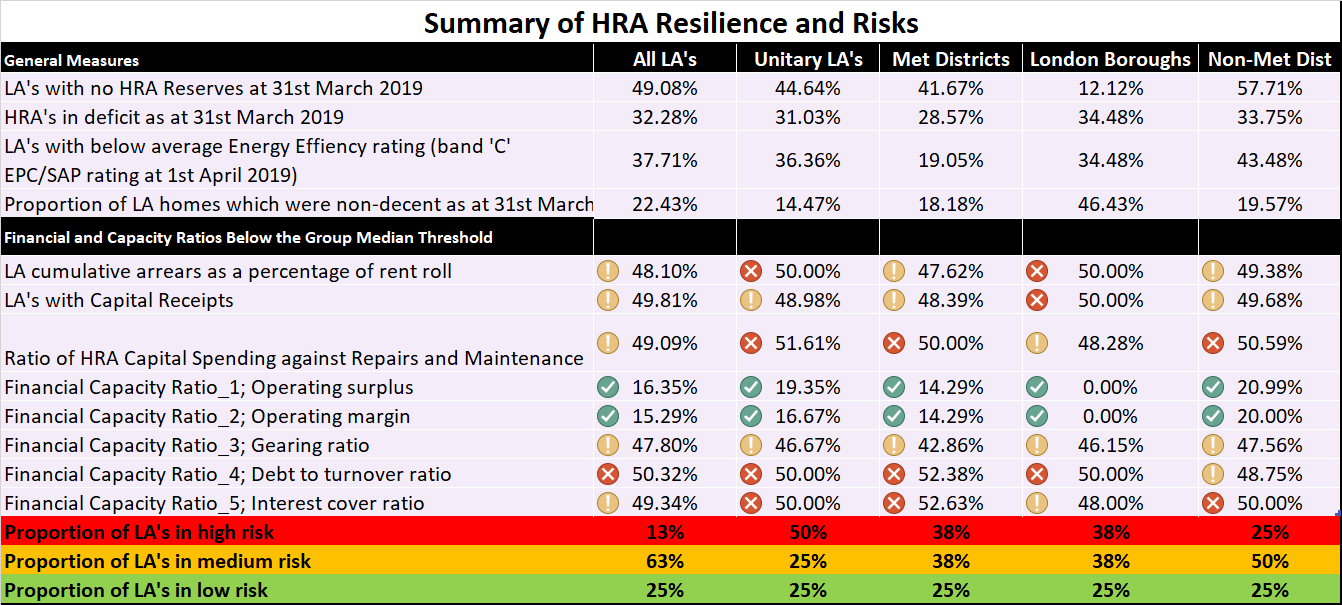

Based on CIPFA's Housing 360 scorecard the financial health of council HRAs can be modelled across a series of resilience metrics. While the scorecard provides 22 metrics to test resilience, in this one example we examined 12 measures, including five financial capacity ratios to give an overview of resilience across England in 2018/19.

Worryingly, nearly 50% of authorities had no HRA reserves as of 2018/19. Across authority types, non-metropolitan district authorities are in the worst position. Non-metropolitan districts and London boroughs also demonstrate a high level of HRAs in deficit. With respect to financial capacity ratios, 13% of all local authorities in England are considered high risk, with unitary authorities appearing to be at greatest risk.

Using the Housing 360 Future Resources model, we can see that council rents are expected to increase following the Government's choice to shift away from rent reduction to subsidised rents. The value of council rent roll is expected to increase by 16% across England, from £6.9bn in 2019 to £8.2bn in 2025. Collection levels are also expected to increase from 94.8% in 2020 to just over 95.3% by 2025. Rent arrears will also likely increase by 0.83% from 2020 to 2025. This equates to a rise in average debt of £235 per property in 2020 to £237 in 2025.

So what next? The first stage in establishing the capacity of councils to build more homes is identifying the investment requirements of existing stock. There are three broad areas to consider:

- Building safety: The Grenfell fire and the subsequent Hackitt Review has forced this up the agenda. Works to replace unsafe cladding, install sprinklers, replace fire doors and install fire alarms all need to be planned and comprehensive surveys commissioned to identify what needs to be done.

- Climate change: Homes will need to be retrofitted to achieve net zero carbon targets.

- Decent homes ‘2' standard: Housing 360 shows that nearly 38% of council stock is not on course to achieve an Energy Performance Certificate rating of C by 2030 in line with the standard. Investment to achieve this target should not be planned in isolation from the need to achieve longer term carbon reduction goals. It may be more efficient to integrate the planning and works for all upgrades to avoid disruption to tenants.

Each authority will have its own pressures. Not every council will have high-rise dwellings and some stock will be in better condition than others. The business plan will already include costings for stock survey and maintenance to which any additional costs will need to be added. There will also be opportunities to attract subsidy and support from the Government such as the £50m Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund which was announced in the chancellor's July statement. The abolition of the debt cap on HRAs provides councils with the opportunity to make their own judgements on their capacity to build more new homes.

Savills has estimated that the national HRA has the overall financial capacity to build around 15,000 new homes per year. In addition to councils investing in their in-house skills and capacity, this will require:

• a long-term commitment to subsidising the building programme;

• greater local discretion on rent increases;

• certainty over low interest borrowing from the Public Works Loan Board; and

• freezing or abolishing Right to Buy.

This is not a quick fix issue. Radical change is needed that will take time to implement. But the longest journey begins with a single step, and councils can only do so much in a policy environment that is hostile to social housing. An urgent and fundamental shift in policy will be needed if councils are to get anywhere near the 90,000 new homes required to meet the housing crisis head on.

David Ayre is CIPFA Property Networks manager

CIPFA Housing 360 provides analytical insight for housing finance, management and planning. Find out more here