Matt Hancock confirmed last month that the government will axe Public Health England (PHE) to create a new National Institute for Health Protection, with a ‘single and relentless mission' to protect the country from ‘external' threats including infectious diseases, outbreaks and biological weapons.

Making such considerations a more conscious and explicit part of governmental responsibility is welcome news, amidst growing recognition of the systemic risks which led to COVID-19. However, such a shift could create a vacuum regarding public health as it relates to endogenous, domestic drivers of health outcomes: a significant component of which is work, the quality of which is known to significantly shape health outcomes.

Work related health inequalities are more pertinent than ever in the context of the pandemic. As the British Red Cross COVID-19 vulnerability index suggests, Grimsby – where the main sectors are ports and logistics, food processing, chemicals and process industries, and digital media – is among the most vulnerable location in the country because of its economy, contra to, for instance, Cleethorpes, which is vulnerable because of clinical factors (e.g. pre-existing health conditions and proportion of the population over 70).

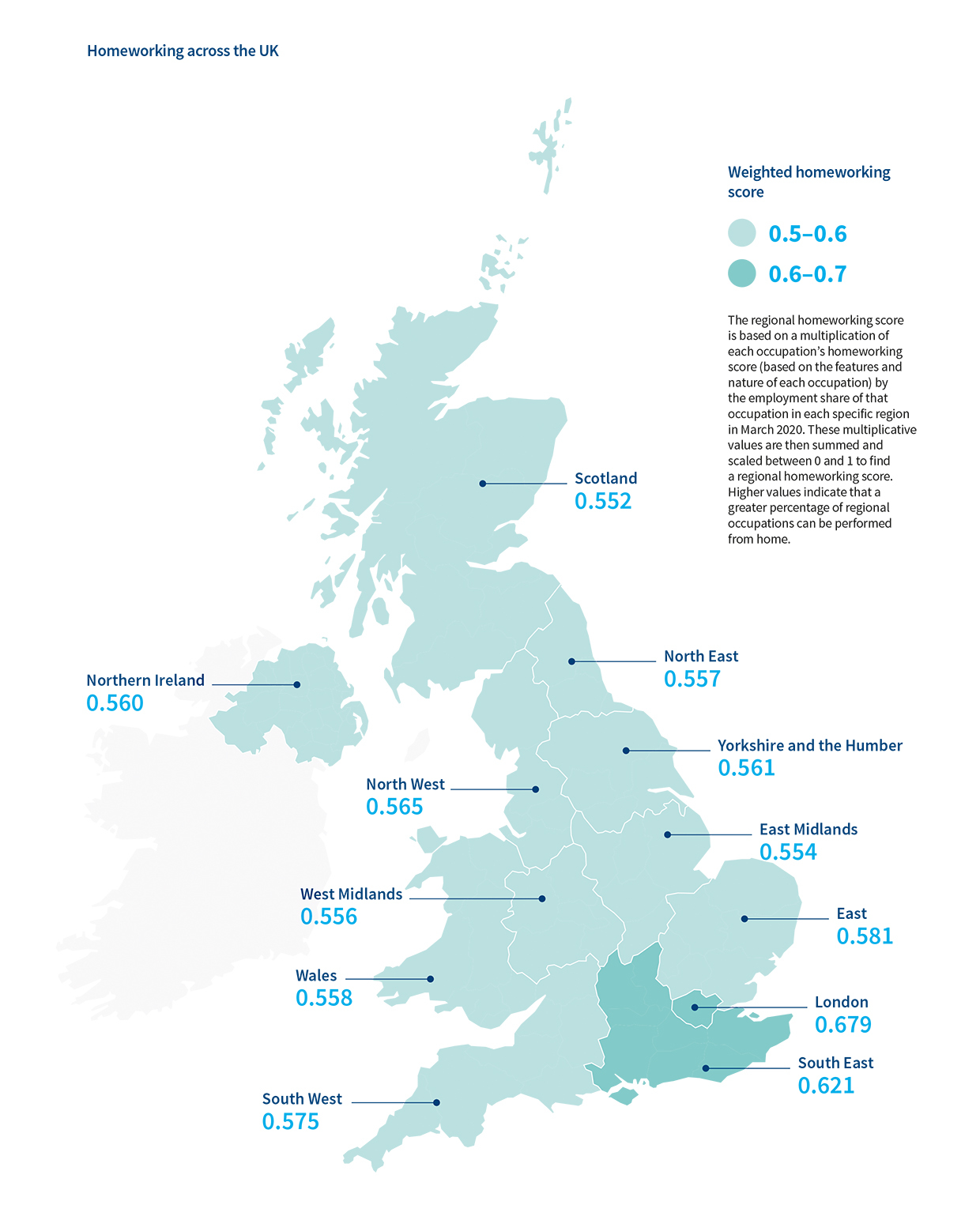

Remote working, affording differentiated shielding opportunities, is also place-biased. As documented in our latest spotlight report, while 57% of Londoners were working remotely during lockdown, just 35% of those in the West Midlands were. This isn't just about different employer choices, either. Looking at the differentially weighted potential for homeworking across the country, these differences reflect the different kinds of work on offer by region, and their suitability to digital mediation.

As local lockdowns continue to shock the economy of places dependent on high proximity work, existing inequalities in access to work will deepen, compounding health inequalities. As we discuss in a recent report, the COVID-19 shock will likely interplay with a slower acting driver of labour market transition, automation. Research has demonstrated that during previous recessions, hightened automation is place-based.

The transfer of public health responsibility from the NHS into local government in 2013 was wise given the role place plays in social determinants of health outcomes. Many authorities have made strides in adopting a ‘wider determinants' approach, resisting the clinically biased core-reporting requirements of PHE. However, a widespread and explicit focus on work has yet to become a normalised. This is undoubtedly linked to the woefully limited labour market shaping powers of local government, notwithstanding the recent proliferation of municipal businesses, a strategy under threat following government consultation on the future of PWLB, and inclusive-growth related procurement strategies.

Public Health funding provided a much needed resource to local authorities in recent years, the loss of which could be devastating. As we move into the brave new world of ‘external threat' focused public health nationally, local areas should be empowered and equipped to respond to the more familiar and endogenous drivers of health inequalities – one of the most significant of which being access to good work. In this context, we need to build

- A clear ask for the forthcoming English Devolution White Paper from the sector. Previous rounds of devolution saw a first-mover disadvantage, with negotiations between government and local authorities happening behind closed doors. To get ahead of the curve and create collective, public asks which are responsive to local needs, authorities should cooperatively develop ‘compacts', mirroring a US constitutional asset IFOW describe further in this report. Compacts should outline shared strategies for the management of further localised lockdowns, and begin to structure asks for industrial, labour market shaping policies which would enable places to ‘level-up' and craft a future of better work, for better public health. If localities are tasked with enforcing local lockdowns, they should also be trusted with designing their economic recovery from them.

- Clarity of vision on the relationship between local health and wellbeing needs, and the active labour market policies being campaigned for as a response to COVID19. IFOW proposed a Community Work Corps, with a centralised programme supporting training and new jobs in care, while also allowing local creativity to shape the broader direction of a new economy. Later this year we'll explore what Grimsby residents would deem good, necessary work in their community if the choice was in their hands.

- Ensure a focus on 'external threats' does not come at the expense of recognisably endogenous drivers of health inequality. For this we need a Work 5.0 Strategy to develop institutional capacity to cope with the compounding disruptions of COVID19, automation, and an impending recession, placing wellbeing at the forefront of rebuilding a more sustainable economy.

If you want to work with us to shape these conversations as a Future of Work Local Leader, please do get in touch.

Dr Abigal Gilbert is principal researcher at the Institute for the Future of Work.