Many local authorities are keen to play a lead role in decarbonisation. But do they have the resources to do so effectively? The National Audit Office (NAO) recently reported that capacity varies widely. Some councils have large teams working on climate and sustainability, but many report lack of workforce capacity as a barrier to tackling climate change. This varying level of resourcing may mean some local authorities are better placed than others to bid for Government funding for decarbonisation, which could widen these gaps.

One of Nesta's core missions is to help reduce household emissions in the UK, so we are interested in local authorities' role in home decarbonisation and how we might help.

The Government recently ran two grant funding competitions for local authorities in England to support home decarbonisation: the Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery scheme (GHG LAD) and the Social Housing Decarbonisation Demonstrator Fund (SHDDF). We looked at where the money has gone, to see if there were patterns among successful local authority bids and whether the funding appears to be following the level of need in communities.

Two-thirds of English local authorities received some funding

Grants were spread across the five types of principal local authority, with district councils receiving the largest number as individuals or lead bodies in a consortium (64) and county councils the fewest (seven).

Proportionally, unitary authorities were the most likely to have an individual grant or to be a consortium lead (51% did so), followed by metropolitan boroughs and London boroughs, suggesting an urban skew. London boroughs were most likely of all local authority types to receive grant funding. We found some evidence that grant winning capability is concentrated in a group of local authorities – 39 local authorities between them won 81 individual and consortium grants (54% of the total).

But the majority took part as consortium members only

One hundred and six principal local authorities (32%) received funding individually or as consortium leads, while 118 (35%) received funding as consortium members only. Giving GHG LAD grants to consortia as well as individual local authorities seems to have enabled a much wider range of local authorities to access funding.

However, some of the consortia are very large (one, led by the Greater London Authority, had 34 including all London boroughs), which suggests activity and funding is probably being spread quite thinly. Information on the size of GHG LAD grants wasn't available for analysis, so we were not able to tell whether larger consortia got more funding.

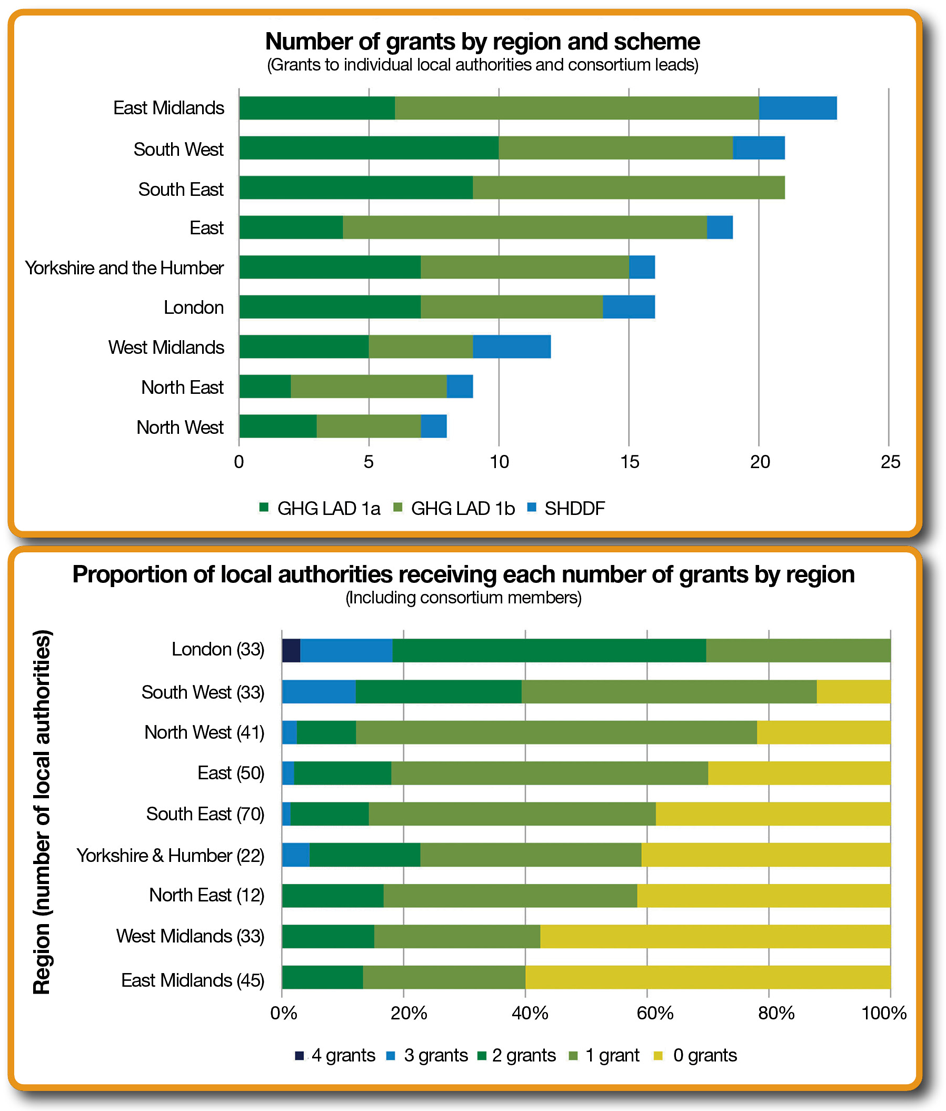

Grants were unevenly spread across English regions

Across the two funds, the largest number of grants went to the East Midlands, South West and South East, with the North East and North West receiving the smallest number. It is important to note that this analysis just covers the number of grants, and not their value, so we don't know the amount of funding flowing to each region (see top graph).

In some regions, virtually all local authorities got some funding, while in others, funding was concentrated among a few councils. All 33 London boroughs received funding from at least one grant (the majority as members of consortia), as did nearly all of the 33 local authorities in the South West.

In contrast, only around 40% of local authorities in the East Midlands received any grant funding, even though this region was one of those that received the largest number of grants overall.

The West Midlands, meanwhile, received a relatively small number of grants, and these were concentrated among a relatively small group of local authorities – again, just over 40% of the region's 33 councils received grant funding (see bottom graph).

We didn't find a relationship between grants received and levels of fuel poverty. The local authorities that received grant funding have fuel poverty rates ranging from less than 5% to over 22%, and overall, the fuel poverty profile of local authorities that received funding is broadly similar to those that didn't. However, the local authorities that got funding from three grants all had fuel poverty rates of over 10%, and the only local authority to receive funding from four grants (Barking & Dagenham LBC) has the highest proportion of fuel poor households in England.

Nevertheless, we also noted that some of the local authorities with the highest fuel poverty rates in England received no grant funding – and all of these were in the West Midlands (Stoke-on-Trent, Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Sandwell).

Some local authorities with large amounts of improvable social housing didn't receive SHDDF funding

The stated aim of the SHDDF was to bring energy inefficient social housing up to EPC C or higher. We looked at whether there was a relationship between the number of ‘improvable' socially rented dwellings (dwellings that are currently EPC D or below and have the potential to be EPC C or above) in a local authority and whether or not it received funding. Overall, we found there wasn't – some of the 14 local authorities receiving grants had high numbers of improvable socially rented dwellings, and others had relatively low numbers.

We also noted that three local authorities stood out as having large amounts of ‘improvable' social housing and had not received grants from the SHDDF – Durham, Wakefield, and Birmingham. SHDDF only made 14 grants, and the grants distributed were generally enough to cover retrofits for several hundred homes in each local authority, so even authorities with relatively few improvable socially rented dwellings had the capacity to make improvements and benefit from the grants.

The data so far suggests some areas with the highest need are not yet receiving funding. We did, however, find some correlation between grants received and deprivation levels.

There appears to be some correlation between the number of grants received by a local authority and its deprivation level in terms of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) ‘local concentration' measure (which measures the deprivation levels of a local authority's most deprived areas). The local authorities receiving the most grants are more deprived, while those with the lowest IMD concentration have not received any grants.

Conclusions

The analysis raises some questions about the effectiveness of competitive grant funding schemes to fund local authority decarbonisation. Although a large proportion of English local authorities received some funding, it is not clear that funding has followed need. This suggests that grants are flowing to those local authorities that have capacity to bid for short-term funding schemes and/or are able to form consortia.

For future competitive grant funding schemes, the analysis suggests that more emphasis needs to be placed on supporting local authorities to take part – for example, by setting longer timescales for applications, and helping those that haven't accessed funding so far to form consortia.

Since some local authorities have been particularly successful so far, this suggests that they might be leading the field, so there is likely to be real value in enabling others to learn from what they are doing.

To help local authorities act strategically in decarbonising homes, we suggest that longer-term funding streams need to be introduced, since competitive bidding is always likely to favour those that are already well placed.

Madeleine Gabriel is mission director (a sustainable future) at Nesta

The Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery scheme (GHG LAD) aimed to raise the energy efficiency of low income and low energy performance homes in England. It was awarded in phases, through a competitive mechanism. Local authorities could apply individually or as part of consortia.

The Social Housing Decarbonisation Demonstrator Fund (SHDDF) was awarded to local authorities in England and Scotland to fund projects retrofitting social housing at scale, aiming to bring homes up to EPC C or higher.

The SHDDF aimed to demonstrate innovative approaches to retrofitting at scale, using a whole house approach, and to generate lessons that could inform the larger Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund, a £3.8bn manifesto commitment, which will launch in October 2021. Seventeen local authorities received funding, 14 of which were in England, with a total of £62m distributed in total.