When Government-appointed commissioners arrive to take up the financial and policy reins at councils who have issued section 114 (s114)notices of, effectively, insolvency, it is worth scrutinising the spreadsheets published by the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB) sitting quietly and unaccountably in the depths of the debt management office of the Treasury.

The PWLB's primary purpose has always remained to provide long-term affordable financing to councils for capital investment projects. As of March this year, the PWLB reported 15,998 current loans to the UK local government sector, with a total maturity value of more than £95.6bn. This amounts to 78% of long-term council borrowing with the rest lent through UK and non-UK banks, negotiable bonds, commercial paper, other councils and undisclosed sources.

But how does this work when major councils, like Birmingham, run into financial breakdown? The Government orthodoxy is that these cases are exceptional and specific local failures of poor decision-making, leadership, management and governance in commercial ventures like property deals, energy companies, or, in Birmingham's case, equal pay claims. What is missing from this top-down narrative is recognition of the Government's own roles and responsibilities in the genesis, incubation and emergence of local financial crisis. And local councils' own assertions of the ‘perfect storm' of rising demand, rising costs, and restricted options for raising income is too generic and easy to characterise as moaning from – and by – an ungrateful sector.

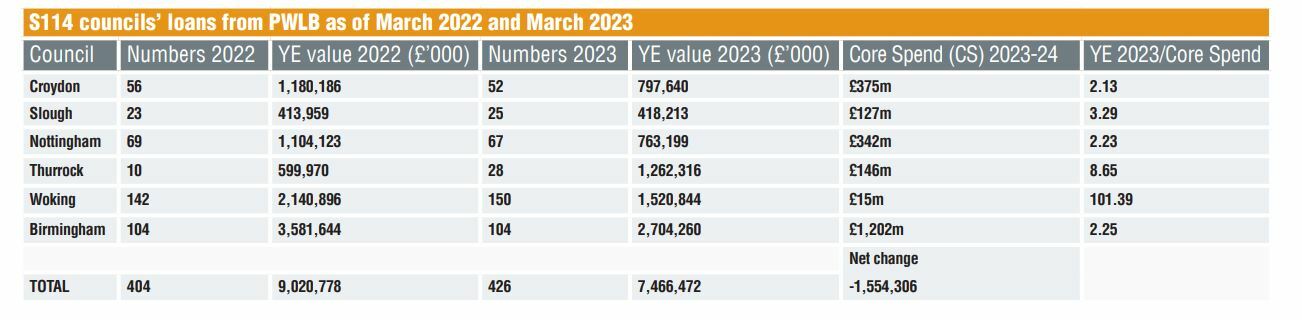

The table below outlines s114 councils' loans from the PWLB as of March 2022 and March 2023 (with s114 councils being those who have entered Government's intervention).

The table reveals major imbalances in how the current PWLB lending system is working and raises major issues of the Treasury's complicity in councils' financial breakdown.

On the crisis's genesis and incubation, of course, someone in Woking BC should be answerable for the 142 loans with a book value of £2.1bn that this £15m per annum core spending council borrowed from the PWLB. But so too should someone at PWLB, the debt management office and/or the Treasury – who extended finance to a council to the extent of more than 140 times its core spending power by 2022.

In terms of sustaining the crisis, the ‘s114 six's' total debt to PWLB fell from £9bn to £7.5bn between 2022 and 2023. Indeed, Birmingham's net reduction in PWLB borrowing is greater than their equal pay claims. As Government commissioners take the financial reins of s114 councils, discussion is needed on the balance between service cuts to vulnerable people, strategic asset fire sales, local tax increases and paying back the Treasury's National Loan Fund. PWLB's lack of due diligence should be as material as local failure.

Most new PWLB loans to Thurrock Council (but also to three of the other six), is not long-term capital funding but short-term 12 month borrowing (more than £1bn in Thurrock's case). PWLB is not meant to be primarily a short-term lender. But it does earn near-market interest on these sums for the Treasury, again while core local services are being cut.

If the PWLB-anchored system of council capital financing is fundamentally broken, what are the reform options for the existing or incoming Government in 2024-25?

First, strengthened due diligence in project and treasury management to ensure debt financing is repayable is critical – literally from Government to councils. While the European Investment Bank (EIB) and UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB) support this for borrowers, PWLB has not done so hitherto and lends to councils simply by virtue of their institutional status.

Second, the ecology and financial resources of institutions providing financing at the sub-national level need dramatic expansion. Formerly, the EIB provided a major source of UK infrastructure financing – more than €165bn by the time the UK triggered Article 15 in 2017. In comparison, the new UKIB's £22bn [of lending] over five to eight years is less than one third of what EIB lending would have been, at a time when the UK requires a real inflation-proofed increase.

Third, overall council financial recovery must address root issues in a highly centralised and dysfunctional funding system including viable core and demand-led funding, and fiscal devolution. The Government's intervention methodology of local service reductions, strategic asset sales and local tax increases must be secondary to local vitality and wellbeing.

Finally, the PWLB needs radical reform or even replacement if it is to be part of the solution rather than the problem. PWLB's long and even its short-term capital financing is necessary. But unaccountable, arguably in some cases reckless, lending is not the way to provide it.

David Marlow is a visiting professor of practice and Andy Pike is Henry Daysh professor of regional development studies at the Centre for Regional Development Studies at Newcastle University (CURDS)

• Additional contributions from Dr Peter O'Brien, visiting professor at CURDS

davidmarlow@thirdlifeeconomics.co.uk andy.pike@newcastle.ac.uk peter.o'brien@ncl.ac.uk